Evolutionary History of the Chicken (pigeon, and other birds) + Domestication

Entertaining the age-old question, “Which came first the chicken or the egg?” was a necessary side note. Now, it’s time to shake a tail feather and get to the story we’ve all been waiting for:

Long long ago, when chickens had teeth…

230 Million years ago, the theropods had begun their rise in two categories consisting of the Ceratosauria and the Tetanurae, both of which had originated by the Late Triassic. Ceratosauria split into the ceratosauroids (e.g. Majungasaurus) and coelophysoids (e.g. Dilophosaurus).

The coelurosaurs include Ornitholestes at the base, and four clades: the Therizinosauridae, the Ornithomimidae, the Tyrannosauridae, and the Maniraptora (Turner, Pol, Clarke, Erickson, & Norell, 2007). The Tyrannosauridae genetic line gave rise to the T-rex, and its living genetic relative, the domestic chicken.

The coelurosaurs include Ornitholestes at the base, and four clades: the Therizinosauridae, the Ornithomimidae, the Tyrannosauridae, and the Maniraptora (Turner, Pol, Clarke, Erickson, & Norell, 2007). The Tyrannosauridae genetic line gave rise to the T-rex, and its living genetic relative, the domestic chicken.

Got that?

- Origional theropod >

- Ceratosauria >

- coelophysoids >

- Ornitholestes (like picture B) >

- Tyrannosauridae (T-Rex)

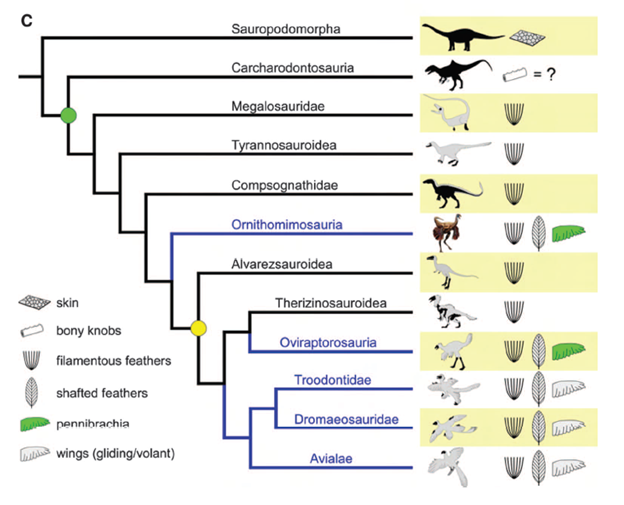

Ornithomimosauria were an average of 4 meters tall; providing reasonable evidence that feathers evolved originally for other reasons than flight, giving interesting insight into the evolution of colorful chicken breeds and social and reproductive behavior today.

The appearance of pennibrachia which are wing-like arms that couldn’t be used to glide or fly (B) suggest wing-like structures may have initially evolved as a sexual characteristic (like courtship, display, and brooding [will define later in behavior]) and only later used for flight. (Zelenitsky, et al., 2012).

(C) Phylogenetic distribution of major feather types and wings/pennibrachia in theropods. The basal most occurrence of winglike structures among Theropoda is in Ornithomimosauria. Green node is Theropoda. Yellow node is Maniraptora. Blue branches indicate clades that possess wings/pennibrachia. Gray wings denote clades in which at least one taxon used wings for aerial locomotion.

(Zelenitsky, et al., 2012, p. 513)

Genetically related: T-Rex, Jungle Fowl to Chicken

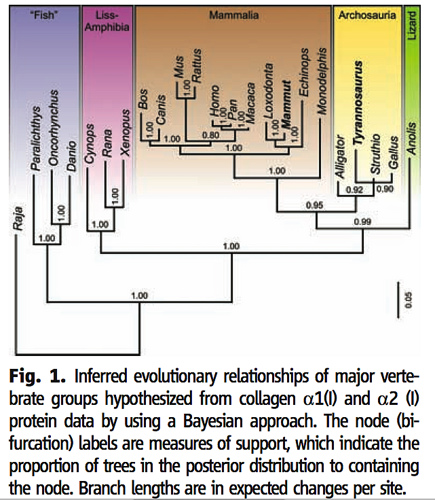

Paleontologist Jack Horner in 2003 unearthed a Tyrannosaurus rex that lived 68 million years ago in Montana and recovered a still-elastic blood vessel from inside a fractured thigh bone fossil. Recent phylogenetic analyses of this isolated tissue by a team of scientists reveals that the closest living relative of T. rex is none other than the domestic chicken. Of seven decoded amino acid sequences from the collagen molecules, three matched chicken uniquely. Another matched frog uniquely, one matched newt uniquely, and a few matched multiple sequences.

Figure 1 shows the relative biologic genetic relationship of peptide sequences extracted from collagen in T-Rex fossils molecules to the DNA of other animals. As supported by currently existing fossil evidence, the T. Rex is molecularly confirmed closer to both modern ostriches and chickens and somewhat more distant from modern alligators.

(Organ, Schweitzer, Zheng, Freimark, Cantley, & Asara, 2008).

Jungle Fowl to Chicken (and some stuff about human culture)

It is not difficult to consider how the wild jungle fowl became the domesticated chicken. Early humans might have shared more of their immediate space with chickens than any other animal. They required no pen. If a chicken was eaten by a predator it would not have been a serious loss. The first domesticated chickens would have wandered away, mated with wild jungle fowl and would come back to their nest. Of course, human populations found that domesticating birds made life easier. Along with the domestication of other animals and plants the need for hunter gathering was slowly eliminated. Permanent settlements lead to an easier life and the ability to purse things other than basic survival. I drew a comic to explain how this might have worked:

It is reasonable to think that the relationship between humans and chickens was rather casual. The shift from wild to domestic chicken would not have been one that required hard work like large mammal domestication events are believed to be, and unquestionably not as dangerous. The transition can be thought of as natural and slow that satisfied chickens and humans. This natural ease of association between humans and early chickens makes it difficult to determine an actual starting point of the domesticated chicken. The domestication process was something that happened in many areas simultaneously. Researchers have not been able to determine a particular place, people or culture where the process of chicken domestication began. Rather the wild fowl might have naturally fit into human civilization – like squirrels do today – and to eventually became the chicken. Humans were more and more stationary in giving up their nomadic lifestyle. One speculation suggests that wild jungle fowl may have entered into human habitat with seeds appealing to their scavenger nature (Caras, 1996, pp. 176 – 179).

Scholars have identified four stages in the “taming” of the chicken for human needs. The initial domestication took place for the human interests of religion and culture as chickens became a focus of folklore, mythology and religious symbolism. The second stage is coordinated with their geographical dispersal resulting in regional breeds. Cockfighting was popular in many parts of the world at this time, like ancient Rome. Stage three is characterized with the increase of industry and agriculture in Europe and North America and created a popular interest in the selective mating of certain breeds. The fourth stage is associated by industrialized farming and poultry capitalism of the twentieth century (Potts, 2012, pp. 17-18).

The Red Jungle Fowl, Gallus Gallus photo from this Bird Watching Blog!

Modern domestic chickens all descended from one of the four known species of jungle fowl or Gallus habituating areas of Southeast Asia, around 50 million years ago. Fossils of the Gallus ancestor indicate they sought and dispersed into warmer climates during periods of glaciation and spread further north as temperature warmed allowing for the evolution of various species and subspecies (Potts, 2012, pp. 7-8). Most research agrees the red jungle fowl, Gallus gallus, today inhabiting northeastern India, southern China, and south to Sumatra and Java, was the most probable to have created the chicken. In addition recent genetic research has discovered that the yellow skin of the domestic chicken was inherited from the gray jungle fowl, Gallus sonneratii, found today in India (Clutton-Brock, 2012, pp. 94-95). This yellow skin color of many domestic chickens supports the theory of multiple progenitors the foundation of the hypothesis several domestication occurred independently across Southeast Asia including inter-species hybridization within the genus Gallus. Chicken domestication initially is thought to have taken place around 8,000 – 10,000 years ago (Potts, 2012, p. 12)

The gray jungle fowl, Gallus sonneratii, a nice grey jungle fowl photo collection here.

According to perspectives of chicken domestication based on mitochondrial genomes (categorized by common haplogroups) from December 2012 the matrilineal history of chickens should be extended to include more than one ancestor The results of the study also showed that chicken domestication was a fairly recent event of at least 3,600 years old in China and dating from around 2500- 2100 BC in South Asia. Gene flow between the wild junglefowl and domestic chicken may have substantially taken place. This hybridization has been observed and plays a role in the history of domestication and development of the many breeds of chickens there are today. Finally, the study provides genetic evidence for independent domestication events in South Asia, Northeast India, and in the area of southwest china and neighboring Southeast Asia (Peng, et al., 2013).

Ceylon jungle fowl G. lafayettei! Thanks for Great Nature Photos, Venki!

As humans and chicken expanded west, the Ceylon jungle fowl G. lafayettei and the gray G. sonnerattii in southern and western India, probably contributed genes to the “original” red jungle fowl early domesticate. Although we may never know what contributed to the entirety of chicken genetic makeup, the domesticated chicken made it into the Middle East and Europe, the basic time-line trail of travel and expected gene exchange seems easy enough to understand:

| Vietnam | by 8000 B.C. |

| Indus Valley, then Sumeria | by 2000 B.C. |

| Egypt | by 1350 B.C. |

| China | by 1122 B.C |

| Greece and her colonies, then the Roman world | 700 – 500 B.C |

| Persia and Mesopotamia | 600 B.C. |

| Britain | 100 B.C. |

(Caras, 1996, p. 177)

Egypt – 1350BC

Egyptians initially use chickens for cock fighting rather than food. Egyptians later developed artificial incubation techniques, involving the burning of camel dung and straw to warm and incubate the fertilized eggs; techniques which were regarded as sacred and kept secret for centuries. Chickens and ancient Egyptians are discussed in more detail in this embryology post.

Greece – 500BC

For the Greeks, according to this infobarrell post, Chicken is considered a delicacy and prestigious food, adorning tables at the various symposia-drinking parties-the Greeks held. The island of Delos, an important chicken breeding area, is esteemed of the Greeks. Pictures of roosters and hens appear on proto-Corinthian (greek) pottery in the 7th century BC – seen here. I wonder if they ever tried canning chicken in a trust worthy presto pressure cooker…

Rome – 250BC

In contrast, the Romans took them to military outposts throughout the Roman Empire for they could tell the future – they were used for making auguries. Sacred chickens were chickens raised by priests in Roman times. Louis (translated in 2007) in the The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d’Alembert Collaborative Translation Project explains, “Nothing significant was undertaken in the Senate or in the armies, without omens being drawn from the sacred chickens. The most common method of drawing these omens consisted in examining the manner in which the chickens dealt with grain that was presented to them. If they ate it avidly while stamping their feet and scattering it here and there, the augury was favorable; if they refused to eat and drink, the omen was bad and the undertaking for which it was consulted was abandoned. The Romans were very careful not to give out false omens drawn from the sacred chickens after the fatal adventure of the person who took it into his head to do so under L. Papirius Cursor, consul, in the Roman year 482.” Photo from this post about Sacred Chickens.

Chickens were used for food, cock-fighting, and religious practices. Around the Mediterranean, archaeological digs have uncovered chicken bones from about 800 B.C. Chickens were a delicacy among the Romans, whose culinary innovations included the omelet and the practice of stuffing birds for cooking. Farmers began developing methods to fatten the birds—some used wheat bread soaked in wine, while others swore by a mixture of cum in seeds, barley and lizard fat. At one point, the authorities outlawed these practices. Out of concern about moral decay and the pursuit of excessive luxury in the Roman Republic, a law in 161 B.C. limited chicken consumption to one per meal—presumably for the whole table, not per individual—and only if the bird had not been overfed. The practical Roman cooks soon discovered that castrating roosters caused them to fatten on their own, and thus was born the creature we know as the capon.

A decline in the importance of chickens accompanied the decline of the Roman Empire. In the post-Roman period, the size of chickens returned to what it was during the Iron Age more than 1 ,000 years earlier. He speculates that the big, organized farms of Roman times—which were well suited to feeding numerous chickens and protecting them from predators—largely vanished. As the centuries went by, hardier fowls such as geese and partridge began to adorn medieval tables (Lawler & Adler, June 2012).

Middle Ages – Europe (decline in big chicken production of Rome)

When Europe later emerged from the Middle Ages, chickens again became more important. It is not known if the chickens that became popular were from stock that had survived in Europe or if there was a re-introduction of chickens from Asia.

Biblical Chicken 7–2 BC to 30–36 AD

Matthew 23 :37 contains a passage in which Jesus likens his care for the people of Jerusalem to a hen caring for her brood. “O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, that killeth the prophets, and stoneth them that are sent unto her! how often would I have gathered thy children together, even as a hen gathereth her chickens under her wings, and ye would not!” Had this image caught on it could have completely changed Christian iconography dominated instead by depictions of the Good Shepherd.

Polynesian Islands and North America 1200 AD

Chickens were first introduced to the New World by Polynesians who reached the Pacific coast of South America, some archaeologists believe, a century or so before the voyages of Columbus. Over a period of several hundred years, cock-fighting became a fashionable sport. Successful owners selected birds to become good fighters and learned a great deal about the care of chickens. But eventually the sport was outlawed, and many breeders turned their attention to developing new breeds of chickens. It is generally accepted that chickens were brought by the Spanish explorers to the Americas. They were readily accepted by the Native Americans and soon had wide distribution. Some of the cultures did not eat them, using them only for cockfighting and religious practices. In other cultures, chickens were used for food (Latshaw & Musharaf).

Cockfighting, a brief history and understanding (cockfighting photos below by: Yoga Raharja)

The sport of cockfighting developed in Asia. This sport is one in which birds are paired and they fight to the death. Big muscular birds had an advantage in this sport than smaller birds. Winning birds provided the breeding stock, so fighting cocks naturally became bigger over the centuries. Indian fighting cocks were imported into England and were the basis for Old English bird stocks, also used for fighting. They, in turn, provided the basic genetic material for the Cornish breed, a chicken with extreme muscling that resulted in a broad breast.

Clifford Geertz wrote Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight and it provides some important understandings of chickens and cockfighting which can be understood is an expression of the functions in Balinese culture through hierarchy and rules.

Photos by a professional photographer in Bali.

“It is because money does, in this hardly unmaterialistic society, matter and matter very much that the more of it one risks the more of a lot of other things, such as one’s pride, one’s poise, one’s dispassion, one’s masculinity, one also risks, again only momentarily but again very publicly as well. In deep cockfights an owner and his collaborators, and, as we shall see, to a lesser but still quite real extent also their backers on the outside, put their money where their status is.”

Between high status individuals

The finer the cocks involved and the more exactly they will be matched.

The greater the emotion that will be involved and the more the general absorption in the match.

The higher the individual bets center and outside, the shorter the outside bet odds will tend to be, & the more betting there will be over-all.

The less an economic and the more a “status” view of gaming will be involved, and the “solider” the citizens who will be gaming.

“If, to quote Northrop Frye again, we go to see Macbeth to learn what a man feels like after he has gained a kingdom and lost his soul, Balinese go to cockfights to find out what a man, usually composed, aloof, almost obsessively self-absorbed, a kind of moral autocosm, feels like when, attacked, tormented, challenged, insulted, and driven in result to the extremes of fury, he has totally triumphed or been brought totally low.” (Geertz)

1492 – Present United States of America

Cockfighting in the United States became illegal but the genetic characteristics of selective breeds persisted. Nevertheless, the red junglefowl has changed little over thousands of years. It was human intervention, however, that produced the hundreds of breeds of chickens today. These purebreds are described in American Standard of Perfection (1998) and Poultry of the World (1996).

1868 Chromolithograph (below) by L. Prang & Co. in Boston Mass features portraits of all known valuable breeds of fowl. Fifty-two types of identified chickens. This is a file from the Wikimedia Commons and is in the Public Domain.

Europeans arriving in North America found a continent teeming with native turkey and ducks for the plucking and eating. These came from earlier chickens brought by the Polynesians. Well into the 20th century, chickens particularly valued for a source of eggs, had a relatively minor role in the American diet and economy. Industrial age of centralized, mechanized slaughterhouses, were used for cattle and hogs for many years while chicken production was still mostly a casual, local enterprise. The excerpt below and the photos it contains from “One Hundred Years on the South Loup: A History of the Arnold Community from 1883 – 1983” and Compiled by Nora Hall Mills was found on this Outback Nebraska blog.

“It is not known just when the first hunters and trappers came into the Arnold area, but buffalo hunters found trappers on the South Loup in 1859, and it is known others were here by the late seventies. By the middle eighties, deer, elk and prairie chicken hunting had become a big business. The Custer County Republican reported six elk and forty deer being hauled to the railroad in the month of November, 1883.” A market hunter in the early 1900’s in Nebraska “Prairie chickens were taken for the eastern markets, shipped in barrels, salted. Chicken hunters were instructed to draw the birds, stuff them with salt and buffalo grass and hang them on the north side of the soddy until they had a load to haul to the railroad.

Fifty homesteaders over in Logan County signed a petition in 1900 to keep professional hunters from killing their prairie chickens and warned anyone seen with a gun and dog to beware, but even so, the wild chickens had all but disappeared by the late 1920’s, replaced by the prairie grouse and the ringnecked pheasant. Landowners south of Arnold stocked their land with the colorful pheasants and attempted to protect them from poachers.”

“Prairie chickens were taken for the eastern markets, shipped in barrels, salted. Chicken hunters were instructed to draw the birds, stuff them with salt and buffalo grass and hang them on the north side of the soddy until they had a load to haul to the railroad.

Fifty homesteaders over in Logan County signed a petition in 1900 to keep professional hunters from killing their prairie chickens and warned anyone seen with a gun and dog to beware, but even so, the wild chickens had all but disappeared by the late 1920’s, replaced by the prairie grouse and the ringnecked pheasant. Landowners south of Arnold stocked their land with the colorful pheasants and attempted to protect them from poachers.”

Farming in early 1900 looked much like this:

In 1900, the Duluth Benedictine sisters purchased an 80-acre plot of land and it became their farm, explains a web history of St. Scholastica Monastery.

Cornish stock was imported into North America, where they provided genetic material for the meaty broiler chickens. Continued selection for broad breasts has increased the percentage of the body that is white meat, the part of the chicken that is prized most by North Americans. The story of the development of the chicken meat industry shows how chickens have moved from one continent to another and how humans have changed the function of the chicken in the process (Latshaw & Musharaf).

The breakthrough that made today ’s massive, industrial bird farms possible was the fortification of feed with antibiotics and vitamins, allowing chickens to be raised indoors. Like most animals, chickens need sunlight to synthesize vitamin D on their own. Through the first decades of the 20th century, they typically spent their days wandering around the barnyard, pecking for food. Now they could be sheltered from weather and predators and fed a controlled diet in an environment designed to present the minimum of distractions from the essential business of eating. Factory farming represents the chicken’s final step in its transformation into a protein-producing commodity. Hens are packed so tightly into wire cages (less than half a square foot per bird) that they can’t spread their wings; as many as 20,000 to 30,000 broilers are crowded in windowless buildings.

The result has been a vast national experiment in factory farms turning out increasing amounts of chicken thus creating an increasing demand. By the early 1990s, chicken had surpassed beef as Americans’ most popular meat (measured by consumption, that is, not opinion polls), with annual consumption running at around nine billion birds, or 80 pounds per capita, not counting the breading. Modern chickens are cogs in a system designed to convert grain into protein with staggering efficiency (Lawler & Adler, June 2012).

USDA 2007 Census Ag Atlas Maps – Livestock and Animals- Number of Broilers and Other Meat-Type Chickens Sold: 2007

Chickens Were Initially Domesticated for Cockfighting, Not Food | Steph's Random Facts

29 August, 2013 @ 11:59 pm

[…] found a fossilized bone of a Tyrannosaurus rex in Montana with what experts describe as “a still-elastic blood vessel” inside. Experts who study the evolutionary relationships among different species and populations […]

Evolution, History, and Domestication of Chicken | Gameness til the End

22 September, 2013 @ 2:46 am

[…] Evolutionary History of the Chicken (pigeon, and other birds) + Domestication […]