I think there is no species whose narrative has been as forever altered by contact with humanity as the rat. Indeed, it’s hard to imagine a life for them without us. Without the excess of our bloated infrastructure to thrive on, I believe that the modern rat would resemble an entirely different creature. Whether or not we’d like to admit it, human kind probably lives closer to rats than to dogs. In that sense the rat is as much a domesticate of ours as we are of it. Where there are people, there are rats. And where there are rats, there are usually people.

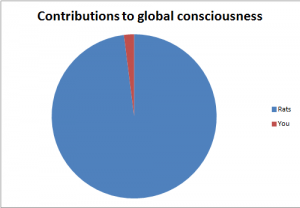

We have always had a relationship with rats to some degree. They live in our cities and are for the most part considered to be vermin. They carried the plague, and while the rest of England stopped bathing, fearful that the illness could carry itself in water, the rats thrived as they have done around us for centuries. A common theory regarding cat domestication is that cats were first brought in to kill mice, and cats comprise most of the internet today. So really, rats have already contributed more to the global consciousness than we ever will. This relationship is illustrated in the following pie chart:

Our living with rats extends into the modern era, with whole professions and minor Batman villains dedicated to the practice of catching the elusive rat.

Right up there with Condiment King.

They are vermin, we say, and should be controlled. We have an aversion in our culture to rodents. They are everything filthy and, along with the fly, go wherever there is decay. And yet, they are evidently clean animals, though the places they live are not. Isn’t that an awful lot like us, though? We place tremendous importance on personal hygiene but I wouldn’t eat off the streets of New York.

Our narratives bleed into one another. It’s no secret that writers have connected people and rodents for a long time. The mouse in the maze. The metaphorical cheese as a goal for the protagonist. The expression, “Like a rat in a cage”, referring to someone who feels like they’re trapped in a situation. The common theme for all of these ideas? Our relationship with the rat today is fully eclipsed by its role in science. They are a reflection of us. Of our progress and our struggles in a modern world. They are a microcosm of our macrocosm in which our great metal skyscrapers become towering maze walls to confuse and preclude us. We see our similarities; thus we extend sympathy to the rat in these situations that it does not find anywhere else.

When we start to talk about animal testing, the rat transforms, in some ways, into an ubiquitous object of modern scientific progression. Perhaps that is fitting; man and rat inventing the future together. A romantic notion, but true nonetheless. I wonder how many discoveries would have gone undiscovered without animal testing. But that raises another question; one that gets pushed to the side more often than not, a question that many people believe is a pointless one. Do the lives of animals injured or killed as a result of animal testing have any weight? Or rather, is animal testing ethical? I haven’t read anyone else’s post yet so I don’t know if someone has already sparked this controversial topic. I’ll do it here in any case. Do we even have an obligation to these animals? Should scientific progress bow to animal rights or are animals a necessary casualty of modern science? Are animals used in testing domesticates or something else? I would fall under the human-centric persuasion that it is a fair, if unilateral, price to pay for the knowledge attained as a result, beauty products and psychological evaluations not included. I simply mean to say that there are legitimate and illegitimate reasons to test on animals and that we should apply our best judgment to decide which is which.