Happy Earth Day, domestication scholars! Celebrate on campus during Earth Week at Virginia Tech. Now, to the RATS.

In 9th grade I memorized this monologue from the Miracle Worker Anne Sullivan when she explains her experience in the asylum, “Rats, why my brother Jimmie and i used to play with the rats because we didn’t have toys. Maybe you’d like to know what Helen will find there, not on visiting days? one ward was full of the old women, crippled, blind, most of them dying, but even if what they had was catching there was no where else to put them, so that’s where they put us. There were younger ones across the hall, prostitutes mostly, with T.B., and epileptic fits, and some of the kind who- kept after other girls, especially young ones, and some insane. Some just had the DT’s. The youngest were in another ward to have babies they didn’t want, started at 13,14. they’d leave afterwords but the babies stayed and we played with them too, though most had-sores- all over, from diseases you’re not supposed to talk about. The first year we had 80, 70 died. The room Jimmie and I played in was the dead house, where they kept the bodies until they could dig the graves.”

I can’t recall the entire piece from memory but, I know it begins powerfully with “Rats,” and that word, the idea of the animal sets the stage for the sickness and death descriptions of a wretched place that follows.

I found the readings about rats very interesting. I’m not sure if I consider them a “domesticated” animal but our evolutionary relationships with them are clearly (and sometimes not so clearly) significant.

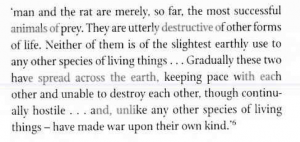

At this point in my “human-animal relationship” analysis career I have come to the understanding that if we follow the expansion and movement of humans we will too find close behind their domestic animals. To understand human development and expansion was to know domestic animal development and expansion and vice versa. This relative rule of thumb is true for the rat. The animal I associate with the bubonic plague. Or as Burt summarizes it in The Multiple Meaning of Laboratory Animals: Standardizing Mice for Cancer Research, “The rat is, as some writers have phrased it, a twin of the human, and their mutual history is dark.”

Rats were not understood to carry disease until the mid 19th century. Seen as thieves and pests to eradicate, Burt discusses the question of how rats came to have such low status, since they were not hated or feared.

Is it because it is associated with danger in our perception? Our relationship to the rat is not just a physical one but one of perception and ideas. The idea that our relationship with an animal can be influenced by simple perception might have serious effects on the next era as humans today do not interact with the animals they eat.

Yet, we admire rats. “The lascivious, greedy and cannibalistic rat…” engages in acts of human sin. They thrive in our gullies and sewers surprisingly manage to avoid toxic pollution exposure. They are smart, adaptable, and even, for some, beautiful.

effluvia plural of ef·flu·vi·um N. An unpleasant or harmful odor, secretion, or discharge.

|

At the beginning of the 20th century human associations of rats was that of fear and that relationship to the natural history of the rat is from the many experiments done with the purpose to eliminate and control.

Reading “the multiple meanings of laboratory animals” I’ve got to say it makes sense that our hate and diastase for the mouse (and.. rat) led them to be our object of experimentation. “MWAHAHA” (sorry, I could not help myself). The reading highlighted just how much our culture and institutions shape our perception, treatment and relationship to mice, rats, and all other animals we interact with in general. It’s a simple understanding yet the many evolutionary, genetic, cultural, and psychological dimensions are complex.

What do you think when you think about Rats?

This is also cool: Once every 48 years, bamboo forests in Northeast India go into flower, and black rats descend upon them, like a plague. Watch it here.

How cool that you committed that passage of “The Miracle Worker” to memory so well that you still remember it?!?!? Playing with rats as a substitute for missing toys is clearly a powerful image. Part of its power I think comes from the rest of the passage, which describes just how squalid, desolate and deadly the institution was for the children. So, oddly, the rats, as macabre toys and diversions, are not the worst elements in this grim childhood…

Plenty of species kill their own kind, and I’ve read that ants and chimps, among others, will make the equivalent of war on each other. And to say rats have never done any good to anyone or for anything is to ignore the thousands, probably millions, of rats and mice that are killed for science and whose deaths have helped find important medical information about diet, medications, operations, genetics, and intelligence.

One person wrote in that spiders kill each other after “sexxing.” At first, I thought she’d written “sexting,” engendering visions of spiders I’d never before imagined. I guess they die happy.