Jonathon Burt’s introduction to Rat prompted many of us to think long and hard about why our 21st-century American reactions to a ubiquitous rodent are so strong and so negative. Looking at the rat in other contexts provides a somewhat different perspective. For example, the Rat is the first animal of the Chinese horoscope cycle.  The Rat conveys many positive qualities to people born under its sign, including leadership, charm, passion and practicality. Year of the Rat people might also be cruel, controlling and exploitative, which reminds us that good and evil are inseparable. One requires the other, and problems arise when balance is disrupted.

The Rat conveys many positive qualities to people born under its sign, including leadership, charm, passion and practicality. Year of the Rat people might also be cruel, controlling and exploitative, which reminds us that good and evil are inseparable. One requires the other, and problems arise when balance is disrupted.

Other cultures have a more practical approach to mice (which belong to the same sub-family of the rodentia order as rats — the murinae). In Malawi poached mice on sticks (captured in freshly harvested corn fields) are considered a culinary delicacy.

But I find that rats and mouse brethren get especially interesting here in the West in the late 19th / early 20th centuries, when creatures mainly seen as “vermin” join the ranks of pets and then become the first purpose bred laboratory animals. Why and how did this transformation come about and why do rats still evoke such complex and strong responses from us? Bill’s fabulous post noted that “there is no species whose narrative has been as forever altered by contact with humanity as the rat.” I’m wondering what would happen if we inverted the query: Where would we be without rats and how has the human condition changed as a result of our interactions with this creature? (As you know, this is a central question of the research projects, and I am looking forward to learning about how everyone sees this issue in terms of the species they’ve been working with throughout the semester.)

Our readings by Karen A. Rader and Kenneth J. Shapiro present us with a good analytical framework for thinking about how the process of domestication shaped human-rat (mouse) interactions over the last century or so. Camilla and Ben have some excellent insights about how rats double as humans, serving as models for humans in biomedical experiments, and anthropomorphic citizens of parallel societies in young adult fiction. Ai Wei-Wei’s zodiac rat, pictured above, portrays the ambiguity of the rat-human divide more powerfully than many words could. Disney’s Mickey, the world’s most famous mouse has long provided scholars with insight about a creature, who in Karen Raber asserts “redefines or challenges conventional zoological and social understanding” (p. 389). Stephen J. Gould’s 1979 essay on neotony still provides an excellent jumping off point for those wanting to learn more.

I’m intrigued by the nexus of domestication, affection, revulsion, and technology we find in contemporary American attitudes about rats and mice. Connor makes some good points about the importance of these rodents to scientific research, and I agree that the contribution to human welfare these animals have made is significant. I think it’s important, however, to consider Shapiro’s and Raber’s analysis closely – regardless of what one thinks about the ethics of animal testing. In Shapiro’s article, we find a nuanced dissection (sorry!) of the synergy between the development of the concept of the “lab animal” and the domestication of rats for that purpose. The application of selective breeding, specific kinds of socialization, and the creation of new “habitats” / confinement systems facilitated the emergence of the domestic lab rat (from the Norway rat) and articulated and shaped the meaning (social construction) of those animals for researchers and human audiences outside the lab. Shapiro’s assertion that rodents make poor models for humans, especially in psychological research presents us with some uncomfortable questions, as does Donna Haraway’s concept of the “cyborg” animal, which is equal parts nature, culture, and technology (think OncoMouseTM).

Finally, for all of their negative cultural baggage, stigma as vermin and unwilling contribution to scientific research, rats can be that most favored of American creatures – the domesticated pet. Rats are clean, sociable, and come in a rainbow of colors. Unlike other rodents sold in pet stores, they rarely bite, and are excellent companions for young children.  The first two rats our family adopted were rescued from the snake food tank at a local pet store (our enthusiasm for raising domestic animals to feed captive wild animals would also be worth thinking through more carefully). In their two years with us they provided endless hours of entertainment and companionship, loved nothing more than to snuggle into a pocket for a nap, and displayed remarkable calm in the face of the cat’s obviously predatory intentions. If they could write about their histories with us, I wonder what they would say?

The first two rats our family adopted were rescued from the snake food tank at a local pet store (our enthusiasm for raising domestic animals to feed captive wild animals would also be worth thinking through more carefully). In their two years with us they provided endless hours of entertainment and companionship, loved nothing more than to snuggle into a pocket for a nap, and displayed remarkable calm in the face of the cat’s obviously predatory intentions. If they could write about their histories with us, I wonder what they would say?

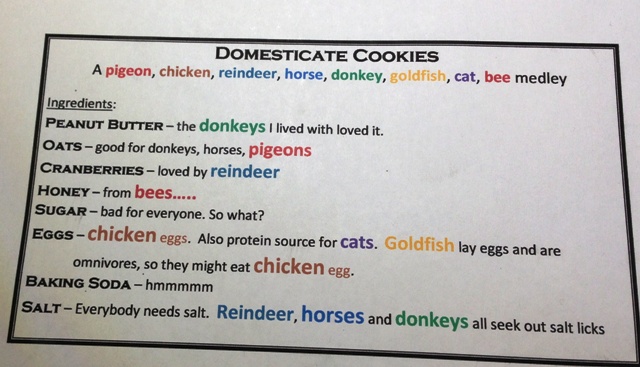

The research projects are complete and posted, and anyone who visits this site should check them out! They share a common structure, but are unique and inspiring in their design and execution. We gave out several course awards, including, Best Overall Project, for Camel, The Most Undervalued and Invaluable Creature (which also won the Best Design category), and “Cutest Pictures” which had strong finalists in Dogs and Their People, Domesticating Wilbur, and Goats. There was firm consensus that the winner in the “Best Title” category was “A Fungus Amongus” (although I must point out that yeast might be a domesticate but is not an animal). Tanner’s chocolate milk reminded us of the importance of lactase persistance in the evolution of human society, just as his project on cattle emphasizes how reciprocal the domestication process is. Peter kept us on our toes all semester (synthetic meat, anyone?), and offers some intriguing insights about the influence of silk on human history and happiness.

The research projects are complete and posted, and anyone who visits this site should check them out! They share a common structure, but are unique and inspiring in their design and execution. We gave out several course awards, including, Best Overall Project, for Camel, The Most Undervalued and Invaluable Creature (which also won the Best Design category), and “Cutest Pictures” which had strong finalists in Dogs and Their People, Domesticating Wilbur, and Goats. There was firm consensus that the winner in the “Best Title” category was “A Fungus Amongus” (although I must point out that yeast might be a domesticate but is not an animal). Tanner’s chocolate milk reminded us of the importance of lactase persistance in the evolution of human society, just as his project on cattle emphasizes how reciprocal the domestication process is. Peter kept us on our toes all semester (synthetic meat, anyone?), and offers some intriguing insights about the influence of silk on human history and happiness.