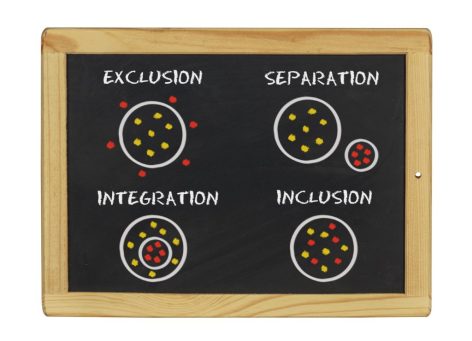

Last week was not one of the best weeks I had this semester. I was trying to cope with the feeling of being lost in my teaching and academic experience when one of my professors referred to the concept of diligence as part of his definition of the qualitative side of our work as scholars. This concept led me to think about the way we perform our daily teaching practice and interactions in the classroom and work environment. I have found out that as the workers in the knowledge production process, we have to cope with the contradiction between reductive pragmatism and immense idealism. Thus, the gap between these extreme approaches is the space where our conscious and unconscious processes are negotiated. I realized that becoming a scholar/teacher required a diligent and constant effort to navigate within this gap by paying attention to our biases and prejudices, by opening space for diversity, and creating an inclusive environment.

The excerpt[i]from the ‘Hidden Brain’ by Shankar Vedantam illustrates an extreme example of the extent to which individuals may act indifferent to immediate human suffering. During the incident at the Belle Isle bridge in Detroit, a woman of color tried to avoid verbal harassment by a man, who later chased her to the Belle Isle bridge with his friends two other friends. Beaten and injured severely, she climbed to the edge of the bridge to save her life. The moment she realized that her perpetrator will not stop and that there is no one to help her, she jumped off the bridge holding on to the slightest chance of her survival. All happened before the eyes of many bystanders, who acted as spectators of a horrific scene rather than witnesses to a brutal crime. Vedantam argues that those who came forward as witnesses later “did not have the insight into their behavior.”[ii] Presenting that our mind works in two modes, pilot/conscious and auto-pilot/unconscious, Vedantam argues that “the autopilot mode can be useful when we’re multitasking, but it can also lead us to make unsupported snap judgments about people in the world around us.”[iii] The “hidden associations”[iv] between new situations and preconceived beliefs start shaping our unconscious when we are as young as three years old. Thus, these connections, centered on the dichotomy of the Self and the Other, determine how we value human life. The moment some of the bystanders changed their minds and admitted their guilt was when they found out that the victim was a mother of a thirteen-year-old.

The Belle Isle bridge incident proves that the life of a woman of color becomes worthy when she had the title of mother, which is respected and sanctified and with which the spectators of the horrific scene at the bridge can identify. Thus, the mind tends to fill the logical gaps with our social and moral judgments, partly shaped by the conventional thought patterns of the society in which we were born, raised, and live. The sense of familiarity or foreignness shapes the way we feel and act within a particular environment. Katherine W. Phillips introduces that it is not hard to understand why people prefer a homogeneous environment over a diverse environment. The conformity of the former is easier to handle than the former: however, Philips invites us to look closely into the benefits of diversity before judging and eliminating it. Thus, she presents some studies showing that diversity increases productivity, and enhances decision-making and problem-solving skills since it pushes us to change the way we think about the problems and issues with which we deal. Philips concludes that “when we hear dissent from someone who is different from us, it provokes more thought than when it comes from someone who looks like us.”[v] Although this idea is plausible, we also need to ask the conditions under which we hear about the dissenting opinion of someone.

In her book, Whistling Vivaldi, Steele shares her experiences in her academic career. Steele presents our perception is segregated by the actor/observer dichotomy. Her example concerning a discussion on racial bias in the university setting illustrates the miscommunication between the administration and some students, who recently become aware of their status as a member of a minority. Steele captures a significant point that everyone is not heard the same, as she switches from observer’s perception to actor’s perception, and shares her realization as follows:

“These students lack motivation or cultural knowledge or skills to success at the more challenging coursework where underperformance tends to occur, or they somehow self-destruct because of low self-expectations or low self-esteem picked up from the broader culture or even from their own families and communities.” (22)

In the face of the rigidity of structures of cultural domination and social organization, I wonder whether the actors would feel safe to make their voices heard in the first place. Also, even if there is enough evidence to invest in diversity in our highly pragmatic professional life, is such belief capable of removing the glass ceiling? I believe as long as we rely on our observer perception, to which Vedantam refers as the hidden brain, we could only come up with suggestions such as “try twice as hard ignore what other people think”[vi] or “just have faith in yourself”[vii] to the struggle of the Other.

As scholars/teachers, I believe we have an important role in shaping the blocks with which we construct the frameworks of culture and social organization. The activity of teaching is part of our everyday practices in which we encounter and reproduce the hidden associations that are the by-products of the history of suffering. Our task is being diligent and self-reflexive, not only with our teaching and scholarly works, but also in our day-to-day interaction with our students and our encounters with the physical, political, social, and cultural structures of the university environment.

[i] See http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=122864641

[ii] Ibid

[iii] Ibid

[iv] Ibid

[v] See https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-diversity-makes-us-smarter/?wt.mc=SA_Facebook-Share

[vi] Ibid

[vii] Ibid

Bibliography

How ‘The Hidden Brain’ Does The Thinking For Us: NPR, http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=122864641 (accessed March 06, 2017).

How Diversity Makes Us Smarter: Scientific American, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-diversity-makes-us-smarter/?wt.mc=SA_Facebook-Share (accessed March 06, 2017)

Stelle, Clause M. Whistling Vivaldi: How Stereotypes Affect Us and What We Can Do. New York. W. W. Norton & Company, 2010.