Grandma, why can’t I ask why?

Let’s keep learning, let’s keep educating, let’s keep asking WHY?

– Carlos F. Mantilla P.

1. “A New Culture of Learning – Cultivating the Imagination for a World of Constant Change” – Douglas Thomas and John Seely BrownGrad 5114 / GEDI Fall 17

Let’s keep learning, let’s keep educating, let’s keep asking WHY?

– Carlos F. Mantilla P.

1. “A New Culture of Learning – Cultivating the Imagination for a World of Constant Change” – Douglas Thomas and John Seely BrownThroughout my school and undergraduate education in India, I was told that education will help me prepare for life and career and that I had to memorize certain facts to be successful. Over grade levels, memorization of principles of PEMDAS and the alphabet turned into memorization of increasingly complex things such as the lanthanide and actinide series, and trigonometric and integral formulae. Yes, you read that right, we had to memorize pages and pages of formulae and facts for each exam and assessments were based not on how well one understood those facts/formulae, but on how well one could memorize and spit them out in the exams. There were no cheat sheets provided in an exam, you had to make your own and sneak them in. Yes, such a memorization heavy atmosphere breeds academic misconduct and cheating is rampant in education in India, but that is a fight for another day.

How was this supposed to prepare me for life?

It is not as if a tax form or a visa application would have a box asking me to write down trigonometric formulae from memory. Needless to say, I identified this critical flaw in my education very early on and my interest and drive to learn was inversely proportional to the amount of memorization in a particular subject. It isn’t surprising then that I did best in English, political science, history, economics and computer science. All of these courses depended on understanding concepts and issues and applying them to create something new for assessment, such as an essay, a report or a piece of code. This lead to a lot of stress in my teenage years, as my parents thought I didn’t want to “study” and “do well in life” and I “sit on the computer all day and am good for nothing”. Note that doing “well in life” meant participating in hyper-competitive Great Indian Engineering Rat Race. I disqualified myself from that race even before it started. All those hours of “sitting on the computer” showed me that there is another world out there, both virtually and literally. It showed me that the education I needed is not easy to get in India and that I had to sail the doctoral seas in another country. I have no regrets for being a below average student, as it helped me understand what I wanted to do in life, which is to be in academia. Since then, I have come to realize that:

Going back to the title for this post and a central theme in readings for this week, if we confuse education with training, are we creating educated trainers or trained educators? My interactions with my peers who entered the workforce in India after undergrad and articles such as 1, 2, and 3, would show that we are creating neither. These articles talk about IT jobs for engineers, but the story is the same in all other engineering disciplines. Don’t get me wrong, both training and education are equally important, but forcing minds to train rather than training minds to think is what brought us to a place where companies have to run massive training programs and re-train graduates before integrating them into their workforce.

The inertia to accept change led to this stagnation in education. The curriculum of most of the programs in India was developed in the 1960s and 1970s, under the assumption that the core curriculum would not change over the years. These programs have expanded to include new areas, but it hasn’t been enough. I hope that as the use of technology increases, students will be able to develop skills outside of class, and instructors will be able to expand their pedagogical toolset. Maybe, one day, India will become a leader in bringing radical change in education.

Until then, I’ll end this post with the following:

“It is not so very important for a person to learn facts. For that, he does not really need a college. He can learn them from books. The value of an education in a liberal arts college is not the learning of many facts, but the training of the mind to think something that cannot be learned from textbooks.” – Albert Einstein

This summer, I worked as the student coordinator for the German Fulbright Student Summer Institute here at Virginia Tech. For three weeks, 24 German Fulbright students toured campus, hiked the surrounding area, and explored the Blacksburg community. During that time, the students also took two courses: Communicating Science and Scientific and Technical Writing. Essentially, these classes are designed to help students better share scientific topics with the everyday person. But on a deeper level, the courses allow students to make connections across cultural barriers, develop confidence, and enhance awareness for others. I never got to sit in on a class, but from what the students told me, every session was full of high energy activities that pushed them out of their comfort zones while also helping them feel connected to their fellow classmates. As a result, the students felt more than comfortable presenting a topic of their choosing to the class at the end of the three weeks – this was set up sort of like a Ted Talk. They’re awesome.

Every time the students talked about their classes, I cringed out of embarrassment – I’d never feel comfortable doing the activities they did! Improv exercises, dancing, singing, you name it. But I soon realized that the “active learning” made them excited to go to class, and therefore, eager to participate, no matter how embarrassing. Plus, a significant portion of course time was spent working in pairs or in groups, allowing them to form special bonds, and a sense of teamwork. While their final speeches were given individually, there was a lot of collaboration that went into the speeches. And that collaboration was evident in everyone’s support and glowing reviews of each other’s work.

Outside of class, we took the students on a handful of tours, from the VTCRC to the CUBE, to the DREAMS Lab. Amazing things are happening at all of these places, most of which goes right over my head. Aside from the language barrier, I think the German students had a good grasp on what was happening during these tours (they’re a crazy smart group!). But even if the topics are complicated, I feel there’s probably a better way to share the research or business models with the public. This isn’t to say I didn’t enjoy the tours. My mind was blown at every stop, and I’m so proud to attend an institution where all of this important work happens. However, if the goal is to get more people interested in such topics, or to at least update outsiders on what’s going on, I think the approach to learning could use some updates. Perhaps the way learning occurs in these STEM classes is more exciting, I don’t know. Whatever the case may be, I hope that I can provide some insight or guidance for these tours in the future.

Is active learning the answer? Maybe. Could we have played some kind of game, created something ourselves, watched a video. . .danced or sung a song? Maybe! But these tours were quick and jam packed, so maybe a simple change in the setup is all that’s needed? Moreover, Robert Talbert suggests in “Four things lecture is good for” that we shouldn’t be quick to make lectures a thing of the past. For tours with these high-level scientific topics, a lecture might actually be ideal – but those doing the lecturing have to understand the purpose and the context. Also, it was evident during every tour that these scientists and researchers are fiercely passionate about their work. And according to Professor James Gee in “Digital Media – New Learners of the 21st Century”, having a specific passion is important. But as the world develops, the information about which people are passionate will change, too. Therefore, what’s even more important than having a specific passion is being passionate about learning. I think if this mentality were more popular, we’d all do a better job at sharing our particular passions because we’d want others to understand them so that we can swap ideas and opinions. It’s quite isolating to be so passionate about something that we aren’t able to share with other people.

Again, I was truly in awe of all the tours during the Fulbright Student Summer Institute. I’m sure I learned a lot more than I realize, but through all the powerpoints, lectures, and scientific vocabulary, all I really remember is being asked to imagine a pig cadaver as a crash-test-dummy at the Center for Injury Biomechanics. Poor little guy!

Ancient Book Pages with Birds Flying Away

(downloaded from Dreamstime, click on the figure to be directed to the original source)

Publishing a manuscript always tends to be a painful process for most graduate students. We put well-tailored figures and organized tables in a manuscript together with years of effort, survive several rounds of reviewing process, and in the end receive an email starting with “Congratulations! You manuscript is accepted for publication on …”. At that moment, you must feel like a rising star in this field, yet this daydream is easily crashed when Google Scholar and Researchgate tell you that very few people read your “intriguing” 10-page paper over the past year with zero citation. You start questioning yourself does your years of research actually benefit the whole community?

Internet gives us easy access to tons of research papers, but access alone does not grant efficient learning. Let’s start with a simple experiment: Download several research papers outside your own field, and I’m sure you can barely make it to the third paper, letting alone remember the major points. Most of the publication in academia are full of jargon and detailed technical processes (even in abstract and keywords), building up a impassable wall between a specific scientific community with the general public. You can imagine the frustration of newcomers in one field, especially undergraduate students, when reading these barely understandable words. At the end of day, our learner-unfriendly publication seems to achieve anything but publicizing our findings effectively.

Guess what? Nobody understand your abstracts!

(click on the figure to be directed to the original source)

How can we possibly change this difficult situation? Recently, most of the journals encourage or even require authors to submit a graphical abstract along with the manuscript. Successful graphical abstract provides a great visual presentation of your current work, which can quickly attract people’s attention within seconds. Readers can easily grasp the fundamental points and broader impact from your work without reading your whole paper. Through this way, the initial screening and skimming processes on the Internet become a enjoyable treasure hunt, significantly enhancing the learning efficiency.

From the researcher’s perspective, creating a graphical abstract is also a refreshing learning process. Graphical abstract abandon the fixed pattern from “Introduction” to “Reference”, and you just need to find a quite place and totally set your mind free! Whether you are an old-fashioned person into colored pencils or computer geek playing with AutoCAD, you can use your own unique way (for example, using avatars from computer games or cartoon) to deliver the most important information embedded in your paper. Once completed, I believe you will have some new understanding or interpretation towards your current work. Besides, the graphical abstract can be further used on digital platforms such as social media and PPT slides for oral presentations (recyclable).1

The process of creating a graphical abstract reminds me of one previous app (Draw Something) on the cellphone. It is so much fun!

Who says only artists can have their portfolio, we scientists and engineering can have amazing taste of art as well! Draw a pair of wings and paint them with your imagination, and they will make your publication fly across the land and ocean.

Reference

Let’s start today’s Blog with an interesting question.

$2 can buy 1 bottle of beer. 4 bottle caps can be exchanged for 1 bottle beer. 2 empty bottles can be exchanged for 1 bottle of beer. How many bottles of beer can you buy with $10?

What’s your answer for this question? 10,15, 18 or more? To be honest, I was quite shocked when I saw people’s answers to it and the way they justify their answers. I tried my best and got 15 bottles of beer for the maximum. But the answer is 20! If you are still wondering how they got this unbelievable number, let me give you some hints. The strategy is to borrow bottles and caps from others and return them back at the end. Now you may say, “Hey, it’s tricky because you didn’t mention we can borrow bottles and caps in the problem!” Yes, I agree with you. But sometimes we need to jump out of our mindsets and be more creative to solve problems.

This is exactly how the students are educated nowadays. Students are encouraged to think more actively and bring out novel ideas, while not receiving enough knowledge to support their imagination. Someone might argue that even Einstein said “Imagination is more important than knowledge.” I believe there was an assumption lying there, which was you already know a lot about one thing. When you know a certain field very well, like Einstein, imagination is something that can help you out develop a new theory or establish a new method. However, for most people, we’re knowing too little to say it. In my opinion, it should just be the opposite. Learning knowledge should always come first. Isaac Newton won’t develop the gravity theory from the falling apple from the tree if he does not have strong background in Physics. Friedrich August Kekulé probably will not realize the structure of Benzene from his dream about snake if he hadn’t been researching it for years. So, I would say knowledge is the basic of imagination.

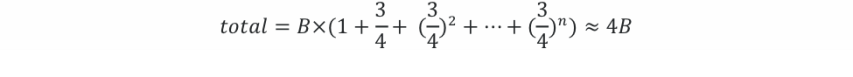

Back to the question in the beginning of the Blog. If you have enough knowledge in mathematic, you probably noticed this is an easy problem to solve by calculation. Each beer you drink can be used to buy ¾ more beers so in general we expect that if you start then you will be able to drink a total of

where B is the number of beer you can buy initially with the money you have, which is 5 in our case. Isn’t this amazing to solve a daily life question with your knowledge?

where B is the number of beer you can buy initially with the money you have, which is 5 in our case. Isn’t this amazing to solve a daily life question with your knowledge?

One of my favorite class in elementary school, involved a teacher whose grading system involved the use of smiley faces and stars on our homework. I fail to recollect the subject, however, I do remember the personalized smiley that I earned on one of my assignments (representation below).

Fig. 1. A close approximation of my personalized badge earned in elementary school.

You should have seen me working on the assignments after that. And this was not limited to me. The entire class of students put in more effort in her class and worked harder on her assignments in an effort to earn their own unique badges. This was the first time when my parents did not have to drag me away from the television to complete assignments or study for exams. Come to think of it, this was the first time I was exposed to the positive effect of gamification in learning, specifically the use of badge.

Figure 2. A(n) (inaccurate) representation of my father before exams

Figure 2. A(n) (inaccurate) representation of my father before exams

Digital badges and their use in online communities is a well documented phenomenon.2 In online communities, users earn digital badges by completing various pre-specified requirements. For example on Stack Overflow, users can earn the Guru or the student badge by answering and asking questions respectively (I managed to get the Tumbleweed Badge. But Shhh! we will not talk about that here). Digital badges serve as status symbols and allows users to distinguish themselves from the crowd. Additionally, earning digital badges increases “positive group identification through the perception of similarity between an individual and the group.”3

Fig 3. My Question Badges on Stack Overflow

Applied to the context of education, digital badges may be utilized to encourage co-operation and self improvement. Students may be assigned badges for helping others as well as improving themselves. Additionally students with specializations in various subject areas may be assigned specific badges reflecting the same. Think of an end of term group paper. A student who specializes in a topic may match with students with other specializations thus increasing the knowledge base of the entire group. In the field of education, Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) such as Coursera, edX etc. award users badges for completing various badges for completing online courses. Other benefits include linking your badge to your LinkedIn profile which aids employers to learn more about their potential hires. Granted that such a system comes with its limitations (Cough! FERPA), yet, in my opinion, it will make learning more engaging.

Fig 4. Linking Coursera achievements to a LinkedIn profile4

Notes:

Change over time or timeless?

As I read, and watched, our readings/videos this week, I was struck by two seemingly dichotomous observations. First that pedagogy changes, and should change, over time (great observation for a historian, right?  ) and, perhaps in opposition, that some pedagogical practices seemingly don’t change. There is almost a timelessness to them. Let me explain.

) and, perhaps in opposition, that some pedagogical practices seemingly don’t change. There is almost a timelessness to them. Let me explain.

I will start with ideas that seem to me to be ageless. As I read and listened to ideas about learning through playing games and tinkering, I really couldn’t help but think that this sort of pedagogy sounded familiar. Exploring, trying something, failing, trying again, becoming frustrated, overcoming frustration and in the process, learning, seemed to me to actually be a very old form of pedagogical practice. In essence, a practice in which a teacher/game designer asks more questions than gives answers and creates the space for self-directed discovery for overcoming problems and initiating critical thinking seems a lot like the socratic method. This method is not unlike Harry Potter as he learned to use his wand.

But to say that pedagogical practices are just a different iterations of something familiar sells short and minimizes the need for educators to adapt to changes over time. I recently asked my sixteen year old granddaughter who is staying with me right now (she attends an online high school which gives her much freedom of movement and a chemistry experiment proceeds on the table in front of me as I write this), “Who taught you about networking with friends through the internet? How did you learn about social media?” Her answer was that she doesn’t remember being “taught” to use the internet for networking. To her, she just always “knew” how to do it (self-directed exploration probably). This is a very different attitude than I have about using the internet – especially for networking. It seems foreign to me, scary and non-understandable, but to her it’s like breathing – easy and second nature.

She is like many of the students that show up in my classroom……..

Times have changed since I first began teaching and I must change along with them. It is scary. It is hard for me to understand. However, I desire to capture the imagination of the digital student (the Reacting to the Past games seem especially intriguing.) Any change, however, will take a step on my part – a willingness to look at my teaching philosophy and be open to change. And while intimidating, I believe change can also be adventurous and rewarding.

(Retrieved from http://thinkspace.csu.edu.au/melissawaldronlamotte/category/etl411/ in a post entitled “The Integration of Technology in the 21st Century Classroom: Teachers Attitudes and Pedagogical Beliefs Toward Emerging Technologies by Chien Yu.)

There is one problem with making learning into a game--you might lose. As you were thinking about the stories and examples given in the readings for this week about getting people engaged in learning using 21st century tools or creative games, did you notice all of the failures and near-failures? Douglas Thomas, who created a… Continue reading I can’t play because I might lose

In A New Culture of Learning: Cultivating the Imagination for A World of Constant Change, Douglas Thomas and John Seely Brown write: “the relentless pace of change that is responsible for our disequilibrium is also our greatest hope.” They move on from there to embrace fundamentally the same mindset that underscored last week’s readings. Even though I want to engage this material with as much sincerity as my teaching practice deserves, it’s a bit frustrating to have read this.

I say that after a lot of consideration… really, I don’t come at this from nowhere. My Master’s of Science capstone project was on an organization devoted to independent video gaming; I’ve designed and coded video games; I’ve showed my students TED talks on the power of gaming, and pretty much all of my good friends are internet / game nerds to some degree. The phenomenon of gaming — and, more broadly, play and creative in a networked environment — is (obviously) cultivated by a technologizing society. Manifestoes like this one tend to position themselves as coming from outside the mainstream. Often they begin with a reference to “traditional” education or societal conventions, the framework which would mark texts like this as ideological outliers — but this is not unconventional by any means.

A much more radical move is to indicate that the unscrutinized acceptance of these technologies necessarily precludes critical discourse about them. Facebook (which Thomas and Brown reference right at the beginning, lumping it in with the very different technology Wikipedia) has become a significant part of many peoples’ lives in the last decade. The sheer magnitude of its role in society means it needs as much constructive skepticism as social sciences and humanities thinkers have accorded to phenomena whose impact took centuries to work toward. But the newness of digital phenomena does not mean that their embrace is in any way unusual. That understanding of them, which is sort of intuitive, is wrong — it just conveniently fits the authors’ ethos. The truth is that in the twenty-first century, with the rate of technological change quickly accelerating, accepting what is new is much easier than thinking critically about it. That’s opening a can of worms that education of all sorts is unprepared to deal with, especially as “digital education” receives a lot of outside attention and funding. “Digital humanities” is more attractive for venture capitalism than non-digital humanities, but I digress…

Right…

I don’t want to keep on this angle for too long. Really this is a recapitulation of last week’s blog, and my soapbox isn’t strong enough to hold me up that long.

My favorite article from this week’s batch was Robert Talbert’s “Four Things Lecture Is Good For.” As a humanities instructor with under forty students in my class, I have the luxury of being able to deliver lectures where I encourage students to raise hands, ask questions, and (if they’re excited enough) even interrupt me as I speak. Nobody has to wait until the end of a twenty-minute diatribe about Virginia Woolf to make a remark about a very specific bit of information mentioned at the beginning. That sort of thing bothered me a lot in high school and during my undergrad years.

Lectures can be awfully boring and pointless, and I think Talbert hits the nail on the head when he notes that they’re bad at transferring information. If I want my students to absorb facts about a writer — and, although I tend to de-emphasize informational learning in general, sometimes I want them to know where Woolf lived when she wrote “A Room Of One’s Own” — I’ll assign them to read certain pages and refer to slides I upload to Canvas. Lectures should contextualize and make lessons “come alive” (if I can use a cheesy cliché). The speaking style of an instructor can convey a sense of purpose and excitement around the course material that’s impossible to give through homework assignments alone.

Having said that, what he meant by “mental models” and “internal cognitive frameworks” was a bit confusing to me. They appear to be conceptualizations from a specific school of educational psychology. I guess I’ll just assume that my hunches about them are accurate. “Internal cognitive framework” sounds like one’s interiorized (and typically unconscious) way of making sense of information. I agree that it is very important to share this with students. In fact I wish my own instructors had been more transparent about how they as students had made sense of the same content they then went on to teach. The thing is — this requires a fair amount of self-knowledge and self reflection. Most people (including most professors) can’t articulate how they learn, at least not in a way that can easily be modeled by others.

Some of my own best learning has come from talking with fellow students. I’ll never forget when my best friend in college, a philosophy major, described to me how she made sense of some of the most notoriously abstruse writers (Derrida, Heidegger and Kant — oh my!). That advice has stayed with me for years. I think about it as I work on the earliest stages of a philosophical dissertation project today.

And — one of my favorite things about programmer culture (and hacker culture in particular) is the bootstrap, DIY approach to learning code. Despite my maybe at times overweening critique, something from techno-culture I can usually support is the moxie it takes to learn a new programming language. The fact that there are still few established conventions for teaching programming, at least outside academia (most of what I’ve learned about code is self- or friends-taught), means that learning how to learn is always part of the deal. Thus you can’t help but explicate “internal cognitive frameworks.” I’ve come up with my own way of practicing coding skills that would be pretty easy to teach someone else, because I know exactly how they work.

Actually, I’d be interested to hear what folks with a more of a traditional academic background in computer science think about that.

***

For those who aren’t in GEDI class, here are the readings I’m responding to:

Douglas Thomas and John Seely Brown, A New Culture of Learning (2011), pp. 17-38 (“Arc of Life Learning” and “A Tale of Two Cultures”)

Robert Talbert, “Four Things Lecture is Good For”

Mark C. Carnes, “Setting Students’ Minds on Fire”

The post GEDI Post II: Infrastructures, Mental and Digital appeared first on .

Make no mistake, teaching is not for the faint of heart. The students we teach can be amazing bright individuals whose energy and hunger for learning can be the reason why we love the work we do and come in every day to teach. However, students also have the ability to throw all of the years you spent mastering your academic craft right back in your face. How is this done you may ask? There is a long list of ways that this can be done but for simplicity, this has been reduced to three nightmare scenarios for anyone aspiring to be a faculty member and teaching. This can be done in three ways, students falling asleep in class, receiving blank, uninterested and confused stares to your questions, and of course, no one laughing at your ‘witty’ jokes that you swore were funny. As noted before, these do not represent all the nightmares that teachers may have, but they are a few.

The question then becomes, as a future professor and faculty member, how can I avoid having more nightmares to tell at dinner parties and luncheons? Well, I wish I could say that the answer is as simple as playing games in class but the reality is that it will take more than simply just playing any game. The games that are played need to have a purpose, learning outcomes and encourage creativity. As we saw last time in class, the thumb war game had outcomes and goals that were achieved. The thumb war activity taught us that games can be an effective teaching tool. However, just like any tool, you have to know how to use it correctly and effectively.

Another way to prevent yourself from waking up late at night due to classroom nightmares is to intentionally think about the design the class. This can be looked at in many ways, but the way you teach your class will also depend on the physical design of the classroom. We all know by now that not all classrooms are created equal and conducive to the engaging learning that we wish to implement in the classroom. If a classroom is similar to our contemporary pedagogy class, then great! Teaching just became easier. However, if you have a classroom with dull tiled floors that are older than you, along with rigid wooden chairs, chalkboard, and small, chopped chalk to write on the board with, then may the force be with you(if you are unfamiliar with that phrase, then I say, “Good luck!”) While that may represent an extreme scenario, it is still possible to have that as a classroom, even today with all the advancements in technology we have experienced.

Even with the physical design of the classroom not being student centered or engagement friendly, it is still possible to make the classroom experience one that fosters and nurtures academic growth and creativity. This is where building lesson plans that encourage active collaboration between student and teacher, and incorporating tools such as games can be helpful. Games allow students to ignore the environment around them and focus on what matters, learning. Games put the power of learning back into the students control and gives them the ability to control their learning adventures. However, as noted before, we need to be careful and intentional about how we use games and when we use them. They need to be structured and with a purpose, and this is not to make the make the game boring. It is to help us achieve the overall learning outcomes we want for the students.

As a bonus, I have one more way we can avoid having teaching nightmares in the future. It will require a different approach and perspective towards facing the inevitable challenges and problems we will face in the classroom. When you see that students are not engaged for a particular reason in class, and they appear to find your class ‘boring’, approach the situation like a problem in a video game. As Dr. Henry Jenkins in New Learners of the 21st century, a video game at the end of the day, presents you with a problem that you need to solve in order to go on to the next level to win. The problem for you could be that your class is boring. That is fine, accept the problem and try to solve it, just like one would in a game. When you solve that problem, you will win, and the reward will be that your students are learning. What better reward is there as a professor?