Public Education: Opportunity or Oppression?

This week’s discussion on Critical Pedagogy comes at a very tumultuous time — the election of a new President and his appointed governmental leaders means significant changes are upon us. The American Education System is one of the first sectors facing serious reform. Secretary of Education, Betsy Devos, looks to overhaul the current public education system by shifting to a more privatized system. Devos reform plan is being met with plenty of opposition from politicians, teachers, and parents alike despite evidence that many public schools are failing and Federal attempts to improve them have yielded no meaningful success. Now, I’m not going to sit here and tell you Devos’s plan is will completely fix all the problems with our education system, but I want to look at the situation with regards to critical pedagogy and how the American Education System came to be in its current state.

Critical pedagogy has been defined as a philosophy of education (and social movement) that has developed and applied concepts of critical theory and related traditions to the filed of education. Critical pedagogy advocates view teaching as inherently political, rejecting the neutrality of knowledge, and believe issues of social justice and democracy are related to the teaching/learning process. The concept of critical pedagogy can be traced back to Paulo Freire’s best-known 1968 work, The Pedagogy of the Oppressed, in which Freire provides a detailed Marxist class analysis in his exploration of the relationship between the colonizer and the colonized as it pertains to education.

Let’s take a quick look at the American Education System. Government-supported and free public schools for all began to be established after the American Revolution. However education was optional and mostly offered at private local institutions or performed at home. This meant that education was not standardized nor was quality education available to everyone. In 1852, Massachusetts was the first U.S. state to pass a contemporary universal public education law requiring every town to create and operate a grammar school. Fines were imposed on parents who did not send their children to school, and the government took the power to take children away from their parents and apprentice them to others if government officials decided that the parents were “unfit to have the children educated properly”. Laws requiring compulsory education spread and now, virtually all states have mandates for when children must begin school and how old they must be before dropping out. Compulsory education laws require children to attend a public or state-accredited private school for a certain period of time with certain exceptions, most notably homeschooling.

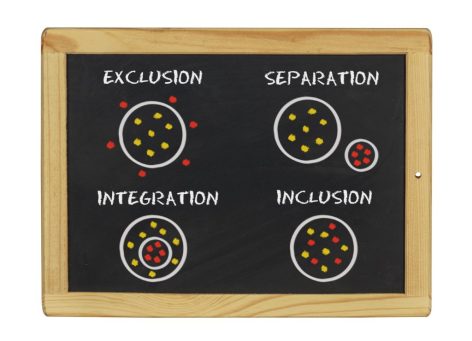

Now that we’ve gotten some of the important background information out of the way, let’s discuss how America’s compulsory education laws have created this colonizer-colonized relationship Freire outlines in The Pedagogy of the Oppressed. By mandating that all children be educated, the Federal government was now responsible for providing a national educational system that was accessible to everyone. This meant that they now have control over the quality and type of content being disseminated to students. Though the public education system was meant to provide everyone with the same educational opportunities, it has furthur exacerbated the educational gap between people of different racial and socio-economic backgrounds.

The is a growing body of evidence showing that the U.S. public education system does not provide the same quality of education to all students. Additionally, similar research shows that U.S. student academic achievement is falling behind that of other countries. Much of this is attributed to the poor quality of education provided by the public school system. Now, there are many quality public schools that provide high-quality education but, unfortunately, they are normally found in areas of economic prosperity. Areas of economic disparity, arguably areas where quality education is most desperately needed, tend to have poor public school systems whose students often fail to meet Federally set academic standards. A factor that furthers this issue is the fact citizens are required to pay taxes supporting the local public schools. For low-income citizens, this means the portion of their income that could have been spent on sending their children to a private or charter school is forcibly invested in public schools. By forcing parents to send their students to school, as well as pay taxes to local public schools, the Federal government is essentially dictating how certain populations will be educated. In the case of those living in low-income areas, they are forced to send their children to the affordable, yet poorer quality, public schools instead of sending them to private or charter schools that may offer a better educational experience.

As it stands, it appears the American Educational System promotes this “colonizer-colonized” relationship, outlined by Freire, which oppresses students via banking education. If we are to free students from this oppression with respect to critical pedagogy, maybe Devos’s reform plan holds some promise? By expanding the options available to families seeking a better education for their kids, parents will have the opportunity send their children to schools offering the best education. Ideally, this will create competition among schools, encouraging them to improve the quality of education they offer. It doesn’t necessarily force students out of public schools, but stimulates the schools to improve while at the same time giving families options if they don’t. It really raises the question on whether continued support of public schools creates opportunity or fosters oppression.

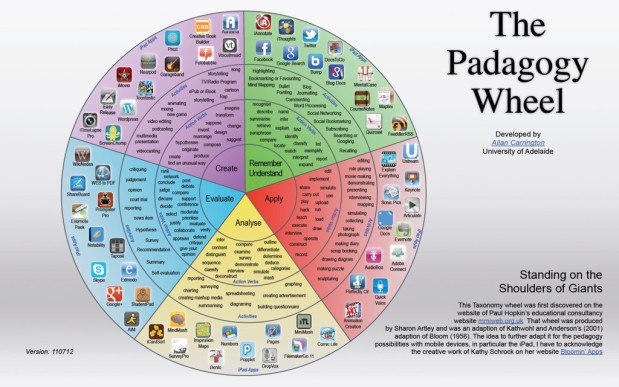

Now, do I believe the “Choose Your Own [Learning] Adventure” method will result in the success of every student? Absolutely not. Similar to the Choose Your Own Adventure books, not all learning paths lead to a “happy ending”. There is always risk involved when one assumes responsibility for their own outcomes. The path to learning is riddled with unforeseen pitfalls and booby traps that can fell many an adventurer. Still, I think such a method is an intriguing alternative that may provide [student] adventurers with the opportunity to actively engage in the learning experience. However, there will always exist a select group of adventurers who prefer to have a “guide” outline their path for them.

Now, do I believe the “Choose Your Own [Learning] Adventure” method will result in the success of every student? Absolutely not. Similar to the Choose Your Own Adventure books, not all learning paths lead to a “happy ending”. There is always risk involved when one assumes responsibility for their own outcomes. The path to learning is riddled with unforeseen pitfalls and booby traps that can fell many an adventurer. Still, I think such a method is an intriguing alternative that may provide [student] adventurers with the opportunity to actively engage in the learning experience. However, there will always exist a select group of adventurers who prefer to have a “guide” outline their path for them.