Grades, Non-Monetary Motivations, and the A Shaped Elephant in the Room

It may come as no surprise that many of the critiques I made last week of Michael Wesch hold for Dan Pink as well. I found his animated video on the existence of non-monetary motivations for work engaging until he made the slightly ludicrous claim that a tech firm allowing its employees autonomy and “self-directed” work ONE DAY PER YEAR was “almost radical.”

Now, I don’t want to beat a dead horse – so I will try not to. I want to make two brief points on this before moving on to the less irksome work of Alfie Kohn.

First, it takes a deeply ideological perspective to be surprised (he calls the science freaky!) that humans are motivated in their work by things other than monetary reward. “Homo Economicus,” profit-maximizers, and other utilitarian conceptions of human behavior are ideological constructions of economists not neutral representations of objective reality. Well-known anarchist Peter Kropotkin made the argument in his classic work “Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution” more than 100 years ago that cooperation and reciprocity characterize human social life as much if not more than purely self-interested competition and maximization.

Second, the idea that there are alternative structures for workplaces that place more emphasis on autonomy, mastery, and purpose and less emphasis on strict hierarchy and ranked performance IS NOT NEW! There is nothing novel about this idea. Karl Marx, Mikhail Bakunin, and countless other anarchist and socialist writers and practitioners have been advocating for this for more than 150 years (not to mention those pesky Luddites). The history of unionism more generally is full of skilled workers resisting efforts by capitalist owners to strip their work of autonomy mastery, and purpose (see: Workers’ Control in America: Studies in the History of Work, Technology, and Labor Struggles by David Montgomery). Furthermore, the way Pink describes corporations putting these ideas into practice, with the goal of instrumentalizing their employees’ creativity and desire for more control to generate more profits, is problematic to say the least.

I just so happen to have written a post on this very topic for the great SPIA blog: RE: Reflections and Explorations. The post “Cooperative Organizations: Toward an On-Going Practice of Democracy” briefly explores what VT’s own Joyce Rothschild has called “collectivist-democratic” organizations. Such organizations come, in my opinion, the closest to the anarchist ideal of truly worker self-directed enterprises in which those who do the work own and control the business. Some even, shock and horror, pay all of their employees the same wage!

Heterodox economist Richard D. Wolff has written numerous books on the topic and runs an organization that helps businesses transition into worker self-directed enterprises. There are more than 200 in the US alone and thousands around the world. The largest and most famous organization of this kind is the Mondragon Corporation in Spain, founded in 1956, employing 74,000 people, and earning around $13bn per year. It’s not perfect, but it’s the “freaky” result of 60 years of attempts to build more autonomous and democratic workplaces.

All of this is to say: cite your sources Dan Pink! Do your research!

Okay, I did beat that dead horse – I couldn’t help myself.

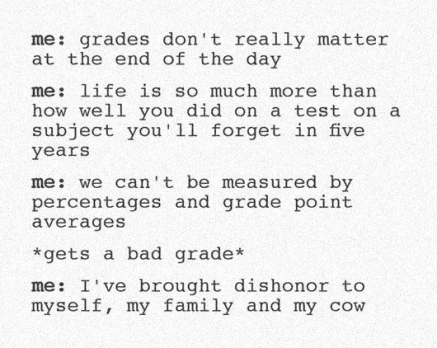

Moving from hierarchy in the workplace (which is both the outcome of grades received in schooling and a continuation of the impulse to sort people by perceived ability, proficiency, etc.) to grades in the academic environment, I was struck by one aspect in Alfie Kohn’s article “The Case Against Grades.”

Kohn quotes English teacher Jim Drier on his transition to a no-grades classroom. Drier said “I think my relationships with students are better” after removing grades. I think about the interpersonal aspect of grading a lot as an instructor. I have felt that the first few weeks of the semester are a grace period in which students can form opinions of me as an instructor and interpersonally in a somewhat natural way. Once the first graded assignment gets back to them though, I always worry it will have damaged rapport I have built with students who didn’t perform well.

I am inclined to think that there is some drop off in effort by students who get discouraged by a poor grade early in the semester and that they may be less willing to come to me for help as a result, particularly if we don’t have a pre-existing relationship. I do think it would be easier to maintain a positive student-teacher relationship if I didn’t have to decide which students are excellent and which are only adequate (and then essentially tell them this).

Asserting my authority in this way through grades is currently a necessity but I certainly do not enjoy it. Kohn discusses various iterations of qualitative feedback and I have tried this as a strategy. On written assignments I try to give substantive comments (both positive and negative) to help the student grow and understand that it’s not “personal.” But, since I also must give a letter grade, I worry, as Kohn points out, that students may ignore the comments and go right to the grade (I myself have been known to do this).

I am persuaded by Kohn’s argument, particularly in the social sciences where I teach, that we should be prepared to “jettison” grades in favor of alternatives. As a grad student, I’ll keep tinkering around the edges looking for those alternatives.