Working with the Open Learning cMOOC (#OpenLearning17) has given me the opportunity to re-connect with one of the most inspirational and talented educators I know. During her long tenure at Virginia Tech Dr. Shelli Fowler developed and taught a graduate course called “Pedagogical Practices in Contemporary Contexts.” A jewel in the crown of certificate programs in Transformative Graduate Education and Training the Future Professoriate, Contemporary Pedagogy brings together graduate students from across the university in a seminar devoted to developing a distinct teaching praxis. Shelli designed the course, which is known across campus as “GEDI” (the Graduate Education Development Institute) to help graduate students acquire the diverse and flexible skill sets they need to succeed and lead as teacher/scholar/professionals in the changing landscape of higher education. It works at multiple levels — as a professional development forum for early-career teachers, as an interdisciplinary discussion of the challenges and commonalities of engaging undergraduates at a Research I university, and as a site of critical engagement over the connections between the philosophical underpinnings and practical application of pedagogy (praxis).

When Shelli moved to VCU in the fall of 2015, she asked me to continue offering the class for the graduate school. I was delighted to help, because the course, its creator, and its constituency had terrific reputations. I also welcome any and all opportunities to work with students outside my main area of expertise. As I’ve learned to teach GEDI over the last few terms I have been inspired by the passion students bring to the linked endeavors of professional development, interdisciplinary dialogue, and critical engagement with pedagogy. I have been invigorated by their talent and willingness to grow and learn from each other. And above all, I have been mightily impressed with the form and substance of Shelli’s curriculum. I have tweaked the corners of the reading list, updating a few things here and there. But the only major change I made to was to shift more of the interaction and content creation into the open and into connected spaces. The arc and substance remain Shelli’s.

Busy as she is in her position as interim Dean of University College at Virginia Commonwealth University, Shelli generously agreed to help facilitate this week, and to answer a few questions about the history and design of GEDI.*

*Pronounced like “Jedi” – as in “GEDI’s use the Force to Cultivate Curiosity.” The current course website is here: http://amynelson.net/gedis17/ Find us on Twitter @GEDIVT and #gediVT.

AN: Tell me about the Genesis of GEDI: Where (and when) did you start, and how did you move from concept to implementation? What was your main goal for the course?

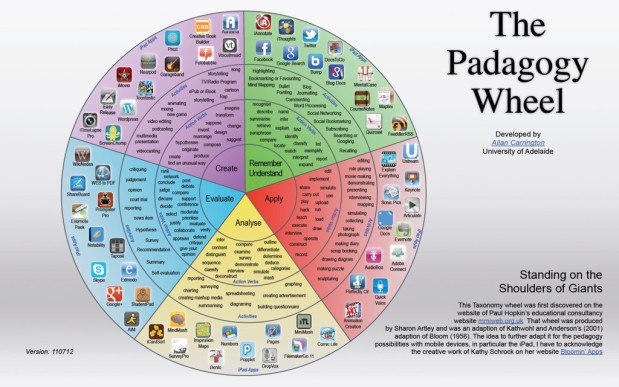

SF: GEDI began in the spring of 2003 as a pilot graduate seminar with around 18 students. I was a new addition to the Learning Technologies division (new TLOS) at Virginia Tech. The VP of my unit, Dr. Anne Moore met with the new Dean of the Graduate School, Dr. Karen DePauw, to explore how her unit might collaborate with and support the new Dean’s Transformative Graduate Education (TGE) initiative. The idea of a professional development experience focused on teaching and learning for the 21st century, one that supplemented and moved beyond mentoring at the departmental and college levels, was born. Because of my work in faculty development and critical pedagogy, I was tapped to create GEDI. The first couple of semesters it was a small graduate seminar and I worked with the graduate student participants to discover what they knew about teaching and learning, what they wanted to know, and how we could co-create a semester-long seminar experience that provided opportunities to move beyond the still over-utilized ‘stand and deliver’ content-delivery approach that informed their disciplines, both in the experiences as learners and, for those who had done some teaching, in the ways they were expected to teach. The main goal for GEDI was to create a dynamic, active co-learning environment that continually challenges us to reexamine traditional teaching strategies and explore active, connected, critically engaged co-learning across the disciplines and in a wide range of learning environments–small and large, face-to-face, blended, fully digital. As such, I really intended from the very beginning to ‘gently disrupt’–a favorite descriptive phrase of mine, the status quo of teaching and learning practices that students suggested were based on ‘we’ve always done it this’ or ‘it’s efficient and easy to assess,’ or ‘just follow the teaching tips on the handout provided.’ Interestingly, the emphasis on (and some might argue epidemic overvaluing of) assessment as the driver for curricular and pedagogical praxis very often leads to over-simplified student learning outcomes and an attempt to standardize assessment in ways that indicate the teaching (and coverage) of material occurred but that fails to gauge student agency and engagement with, or ability to apply and build upon, curricular knowledge. What was unexpected was how quickly the course grew. By the third semester, the course had gone through the university-wide approval process and became a three-credit, graded, semester-long graduate seminar, GRAD 5114, and a core requirement of the “Preparing the Future Professoriate” nine-credit graduate certificate. This is not a GTA workshop or a college teaching: tips and tricks one-credit course that are common at many institutions. GEDI is a dynamic graduate seminar taught each semester. Until I left Virginia Tech in May 2015, I worked with approximately 90-100 graduate students each year in the course. Doing paradigm-busting with GEDI Knights (as they began to call themselves) has been a great experience for me as both a teacher and a learner. While I love the challenges and opportunities of my new gig at VCU, I miss–and will always miss–the unique TGE program at VT, all of the remarkable GEDIs and the opportunity to work with and learn from our future faculty in that arena.

AN: The syllabus presents a lovely balance between the practical and the theoretical. We start by talking about the mechanics of connecting online via the website, which makes for an easy segue into the concepts of connected learning and active co-learning, which makes it easy to problematize and interrogate some pretty important and often unexamined assumptions about the significance of what we as faculty “do” in our classes, what traditional assessment modalities do (and don’t do), and even what we mean by “learning.” These meta-level issues become concrete in discussions about authentic and sideways learning, and by examining how different teaching modalities work on the ground. Then students have the opportunity to integrate all of this into a learner-centered syllabus. How did this particular configuration of topics come into being and how did you determine how best to integrate the theoretical and applied components of the course?

SF: The exploration and development of one’s own teaching praxis is a central focus of GEDI. A critically engaged Freirean approach requires us to embrace the ways in which our theory must inform our praxis, but also reminds us that our teaching experiences in different contexts must also inform our the theoretical approaches. The specific sequencing of topics on the GEDI syllabus evolved with input from the graduate students. The focus on disrupting unexamined status quo practice is a constant current, no matter what activities and co-created deliverables. That requires reflection, of course. A critically self-reflexive awareness of who one is as a teacher, of how one’s ‘teaching self’ is read and misread, and empowered and/or disempowered, is an important part of the process, too. That work begins in week one of the seminar and informs the work we do together in the readings and the creation of curricular materials that students do relevant to their current or future teaching.

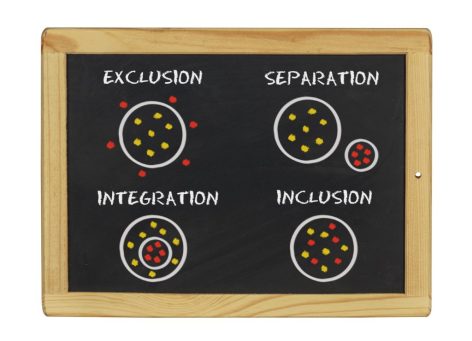

AN: I’m also struck by how the intensity of the course builds through the first seven weeks (and the syllabus project). The topics from these weeks lay the foundation for heart of the matter — Inclusive Pedagogy and Paulo Freire’s Critical Pedagogy. Why are these two topics so important and how do they inform your own teaching praxis?

SF: While an inclusive praxis informs all we do in GEDI, I discovered from the GEDIs that the most honest, deep-dive, open and vulnerable engagement with the topic of diversity, social justice, equity, inclusive excellence occurred after the community of co-learners had been challenging themselves and each other of less fraught topics. We become better listeners, more attentive to the cultural differences among us, when we’ve been doing some collective ‘paradigm-busting’ as a learning community. Rather than begin week one right out of the gate with Freire and inclusive pedagogy–a focus that might unintentionally be (mis)perceived as a prescriptive methodology when a Freirean praxis is intentionally non-prescriptive and essentially an anti-methods pedagogy–GEDIs begin by exploring the broader category of teaching and learning in contemporary U.S. higher education (or K-16 +). They begin to reflect and interact and support and challenge as they discover or articulate what they think and why in their blogging and as they begin to challenge unexamined assumptions about what teaching should be or what constitutes learning. In my work, adapting a Freirean pedagogical praxis is essential, regardless of disciplinary field(s) or course content. The very difficult work for all of us is to invent and (re)invent our praxis so that it is dynamic, rather than static, and stays attentive to equity and access and social justice, domestically and globally. In the GEDI seminar, we begin that process and intend for it to shift and evolve not just throughout the remainder of our seminar but over the span of our teaching.

AN: After the heavy-hitting weeks devoted to inclusivity and Freire, the momentum again shifts in more practical directions. Once again the “deliverables” (a teaching philosophy statement and Problem-Based-Learning / Case study assignment) find powerful undergirding from meta-level framing at the same time they are shaped by very practical “how to” thought-pieces and flowcharts. How did you develop this part of the course in ways that speak to future faculty in all fields — the engineers and other STEM specialists as well as those of us working in the humanities and social sciences?

SF: One of the things that occurs with the move back to what the GEDIs affectionately refer to as ‘tangibles,’ (items such as those you name above that they will use as they construct, or reenvision, their teaching praxis), is a rethinking of the ways their assignments reify traditional power structures in our learning environments. In GEDI, the meta-level framing encourages participants to foster collaborative and inclusive learning environments not just via their syllabus redesign, but in their PBL/case study assignments, for example, with the integration of ethical dilemmas that require students to navigate the complexities of systemic inequities as they learn and apply content to become problem-solvers and problem-posers, including in the STEM fields. I have found that GEDIs in engineering, the sciences, and vet med to be some of the most think-outside-the-box innovators when provided the opportunity to do PBL/case study/ethics curricular design.

AN: The last thing I want to comment on and commend is the way the final module (on ethics in the 21st-Century academy) bring the student back to the notion that we are all in this together. As faculty we face the same challenges and imperatives as our students. We need to commit to learning from and with each other, and to identifying the best ways to make our educational system more humane, ethically oriented, and responsive to a rapidly changing world. Would you like to speak to this?

SF: We are facing similar challenges and imperatives, you’re right. The final curricular segment in GEDI uses a Parker Palmer article, “A New Professional: The Aims of Education Revisited,” to spark awareness that we as faculty need to foster learning environments that encourage learners’ sense of agency and their understanding that their actions as (future) professionals always have ethical repercussions to which they should attend. And that is the same for those of us in academe, too. It is increasingly important in this current moment–how do we best leverage the power of networked co-learners to build and to shape more humane, ethical, equitable, and responsive educational opportunities and non-institution-like institutions of higher ed? One of my takeaways from working with GEDIs is that it is possible to do this if we value working with and learning from our students.