Category: Week 12 – Attention and Multi-Tasking

Dissertation & Distraction!

“All profound distraction opens certain doors. You have to allow yourself to be distracted when you are unable to concentrate. “- Julio Cortázar

What I planned for the day:

& What I ended up doing:

That may be… a (Joyful!) distraction or a refuge!

Week 10: “The Dreaded Teaching Statement”

First things first, I really should not have read an article called The Dreaded Teaching Statement days before actually writing my own teaching statement. That was not a good idea at all. Also, for anyone else out there who plans to write or revise their own teaching statements, don’t do what I did unless you want to end up like me, panic-writing one just to have something for feedback and feeling deeply insecure about it.

Now that I’ve gotten that out of the way, here’s what I’ve got so far:

Creative Technologies lies at the nexus of music and visual art, engineering and design, high art and technology. As such, the students in my field are also in a liminal space between these fields, which makes the formation of an identity more difficult. My role as their teacher is to facilitate their growth as both students and artists, designers, technologists, engineers, or whatever they choose to become in the future. Whether they enter my classroom with a concrete vision of their future role in the arts or sciences or not, my job is to ensure that they have the confidence, the portfolio, and the tools they need to realize that vision whenever it comes.

In the classroom, facilitating looks like the act of paying close attention to each and every student, how they speak or remain silent, how they process the material covered in class, how they create art, what that art means—both in their own eyes and in the eyes of others, and the evolution of their artwork from the beginning of the semester to the end. It also looks like ensuring that each student leaves my class with whatever technical skills they need to continue down the path to their degree, and the confidence that comes with the solid acquisition of those skills.

In research contexts, facilitating looks like collaboration. Becoming part of a larger whole is one of the most rewarding aspects of my research. As a sound designer, a visual artist, or a designer, the part I play in a large-scale project is often unique and gives my colleagues a new way of perceiving their research. Faculty and students who may not have considered the importance of sound or design in their research are often the source of rich conversations in which we both gain knowledge and a wider view of our fields. It is this exchange of ideas that motivates me to remain in the liminal space between disciplines, forging valuable connections and being exposed—and exposing others—to new ways of thinking and being in the world.

I’d love to know what you think. Feedback is a great thing!

Baby Steps,

-Jasmine

I Multitask, Not

Most of the time I am reading through articles and blogs, I am learning something new. Then there are times when I can relate to an article. However, there are rare times, when the article says exactly the same thing I wanted to share for so long. It is so good to read them and realize that your feelings have been expressed somewhere by someone.

I am talking about an article on the myth of multitasking. I was never good at multitasking and that article helped me realized the truth: multitasking does not exist. One can do many tasks switching quickly from one to another but one can only do one task at a time. Of course, the tasks that either have been mastered or that don’t require the same parts of the brain may be performed simultaneously.

I have been told by many people that they can multitask like listen to me, understand it, reply back and still continue the other work and every time I used to ask them how they can concentrate on them at the same time, I would just hear some arguments, like it is all practice or you just have to train your brain, which were not convincing enough. Well, I have the answer now: they weren’t concentrating. They may be good and quick at switching but they can’t be doing all of it simultaneously. When we think of multitasking, one important thing that we tend to forget, we are humans. A machine may be designed to complete several tasks at the same time with different memory allocations for different tasks but we still have one brain with limited nodes. The brain has limited sections and can only handle a number of tasks. Even our machines hang up at times when they are overworked even if they are designed to perform such tasks. So it makes sense that humans fail at that as our brains are not designed for that.

I am not sure about future and with evolution may be the brain’s design is modified so much that humans can multitask. But right now, if you were trying to write a blog/comment while reading this article (or a couple of others on multitasking: 1, 2), discussing with a friend and listening to the podcast on the myth of multitasking (in case reading was not enough), stop right there. Do them one by one and you will get the most from all of them.

Opening the “Canned” Curriculum and Critical Pedagogy

I am surprised that the open educational resources (OER) movement has taken so long to take hold. Having the involvement of the students and other teachers in the course’s materials would give continual improvements. Students have the ability to directly respond to the materials at any moment, not just at the end of the semester in a course evaluation. This openness to critical feedback keeps the curriculum alive and responsive to the students, and gives more ideas to the teacher on what is working for students and what is not. Teachers benefit, students benefit, and the public benefits. How did OER not become the norm? Instead education and knowledge is often regarded like a state secret, only shared on a “need to know” basis. Disagree? Then why would a large-scale learning management systems (LMS) like Canvas show only 3 classes when searching for “CS”? There must be close to a thousand of those classes hosted by Canvas. Those classes can never be used by anyone else now, the class is considered ‘expired’, like a food. An instructor could restart the class for next semester, but they always retain all visibility, control, and restrictions on the course.

Perhaps educational resources should work towards the same progressive structure as academic publishing. Academic works can have a lineage of citations that can be clearly followed to find the origins, modifications, and improvements of the idea. Education materials could be similarly referenced on and expanded upon, and high quality content would become popularized in this same manner. There is one central issue this could cause though. Popularity leads to the homogenization of classes, tempting teachers to be less individualistic, creative, and adaptive in their classes. Students who do not fall in the majority target audience also would be disadvantaged in these classes unless the curriculum is carefully structured. If educational materials merely adopt the academic publishing system, they would inherit the same issues there as well: restrictive access and price gouging. This is why the current academic publishing model is not a good destination for educational resources to move towards. The open access model does not have these concerns and would promote reusing and remixing of the course content. This is how to bring education to the masses, not through having “gold subscription member” tiers.

Side note: I wonder how did universities shed the responsibility of textbook costs onto the students? College students must be able to take care of textbooks better than young kids. But every high school and middle school I’ve heard of pays for their students’ textbooks. Perhaps this is a consequence of the predatory professors who require the most expensive and newest version of their own textbook for their classes. Universities may have refused to fund this practice, but could not prevent it, so it offloaded the expense down to the students.

Mindful of Distraction

Distractions abound in our technology-infused world. Whether they are supplied by our cell phones, laptop screens, or the pervasive presence of TV screens, it’s clear that the speed of modern technology has had an effect on our neurological perception. Regardless of any philosophical argument of whether this change should be embraced or resisted, its existence is undeniable. Part of what makes these distractions so challenging is that the technology is so ubiquitous that their presence is no longer anomalous. Technology, the connectivity it affords, and the distractions it enables is a normal part of life in the world today.

Successfully navigating this stimulation overload requires mindfulness. As Sharon Salzberg states in her article Three Simple Ways to Pay Attention, “mindfulness does not depend on what is happening, but is about how we relate to what is happening.” I like this description as it pertains to the distracting nature of technology because it doesn’t impart a value onto the psychological shift in how we perceive the world. It only asks that we acknowledge and accept that such a shift is taking place.

It’s especially important to incorporate this mindfulness into our pedagogy in the classroom. Doing so helps cultivate a learning environment that is aligned with the realities of the non-academic world. Enforcing policies that limit the use of technology in the classroom can be effective towards mitigating distraction, but avoiding this challenge offers little to students as far as methods of managing the distractions they encounter in other facets of their lives. A lot of what made my favorite teachers so impactful was that the lessons they taught had applications that transcended any particular field of knowledge. I believe that as a teacher in the current technological climate, I have an opportunity to instill a mindfulness in my students regarding their interaction with technology and its constant tug on their attention.

Ideological cogitations aside, I’ve found it challenging to tackle these distractions in the classroom and make no claims towards knowledge of the best practice. I don’t think prohibiting technology is the most forward-thinking policy though, since the technology is unlikely to disappear. There are also many benefits to working with technology. Clive Thompson’s account of human/computer chess teams was illuminating and exciting. We work with computers in almost every aspect of the class I currently teach. They enable us to record and edit videos and animations, manipulate digital imagery, model virtual worlds, develop custom software, program electronics, create websites, and a multitude of other things – all of which is pretty amazing given the number of times I died of cholera on the Oregon Trail in elementary school.

Yet they are also undeniably agents of distraction. Being mindful of this requires awareness and intention. I think it deserves more than just a bullet point on the course syllabus and would be more effective as a discussion that gets revisited regularly throughout the semester. Developing mindfulness towards distraction enables students to be self-aware. In turn, this awareness provides autonomy over whether or not to engage with a distraction. The trick, which I’m sure I’ll always be revising alongside my experience, is to inspire students to actively make the choice to tune out distractions for themselves.

Open Pedagogy

After listening to the Teaching in Higher Ed podcast with Dr. Rajiv Jhangiani, I went looking for a definition of ‘open pedagogy.’ Though I wasn’t able to find one clear definition, it seems to me that the goals of open pedagogy are to engage students in their own learning, and to overcome barriers to education (e.g. cost).

In a TEDx talk, David Wiley says “teachers who are the best teachers, are the ones who share the most completely with the most students.” His point here is that educators should be open in sharing their expertise and experiences. After all, you can “share [your expertise]… without losing it.” Education is about openly sharing ideas back and forth, and collaboratively creating new ideas.

The use of open educational resources (OER), including open textbooks and open access journal articles, can substantially reduce costs of students. Students may find themselves asking: “After paying the high price of tuition, why is the information I’m supposed to be getting still behind a $1000 paywall?” Even worse, the additional cost may prohibit some students from being able to afford to enroll.

Traditional textbooks often get updated every 5-or-so years. Often for introductory textbooks, the new edition of a book might simply rearrange the order of the chapters, or add a few new figures– which probably isn’t worth the $150 price tag. I realize the need for updates can vary by field and sub-field. For fields that are rapidly changing, open textbooks may also be advantageous because they can be revised by experts right away instead of waiting five years for a new book to be published.

Machines are tools and tools can ONLY be tools

Clive Thompson’s reading reminds me of a very interesting question: it is possible that robots or other machines can replace humans as teachers in the classroom in the future? It is not a new question, many fictions, movies, and comics imaged this scene before. Arthur Radebaugh, an American futurist as an illustrator, showed his ideas about the role of machines in the futuristic comic “Closer Than We Think” in 1958 and 1960:

“Tomorrow’s schools will be more crowded; teachers will be correspondingly fewer. Plans for a push-button school have already been proposed by Dr. Simon Ramo, science faculty member at California Institute of Technology. Teaching would be by means of sound movies and mechanical tabulating machines. Pupils would record attendance and answer questions by pushing buttons. Special machines would be “geared” for each individual student so he could advance as rapidly as his abilities warranted. Progress records, also kept by machine, would be periodically reviewed by skilled teachers, and personal help would be available when necessary.”

Arthur Radebaugh’s push-bottom school (Matt Novak, 2013)

“Compressed speech” will help communications: from talking with pilots to teaching reading. Future school children may hear their lessons at twice the rate and understand them better!

Arthur Radebaugh’s robot teacher (Matt Novak, 2013)

In most case, we see machines as tools to improve efficiency, and education is no exception. But what is worrying is that robots and machines don’t have human emotion, they follow specific procedures and standardized tasks. Would it kill the curiosity and creativity of the students? If robots and humans can work together as teachers in the classroom, then where are their boundaries? Although I strongly support the use of machines to help to teach and learning in the classroom, I object to the machine playing a leading role. Teachers are not only teaching knowledge, their personal charm and thoughts can also affect students’ perception of themselves, the world, and the values. Many people dream of becoming a teacher when they are young, is it because they worship their teachers? However, who will worship a robot? Machines are tools, and tools can only be tools.

It’s time for institutions to Design/Test/Iterate/Deliver/ Change

Multiple of the aspects of what Dr. Jhangiani discussed go beyond the walls of an institution:

- Access to digital technology and the digital divide

…and to ideas that run counter to the value proposition of institutions:

- A time-tested curriculum and faculty

- Learning on one campus

– – – – – – – – – – –

The three bullets above are interrelated, but students, professors, parents, and administrators have complex interests that only partially overlap.

Students experience the burden of a textbook (or 3, 4, or 5 textbooks) differently, but we know that some students may struggle to afford a textbook.

We’ve learned that one aspect of a learner-centered syllabus is having student input on the content.

Some professors want to explore new methods, but feel constrained by their institutions. Some parents would not be thrilled to learn that their child “was the guinea pig” in Fall 2018 Intro to Biology. Some administrators are concerned about whether the accreditation for a program will continue if professors are constantly testing new methods and content.

Professors at campuses that are part of consortia (think the Colleges of the Fenway) can leverage (and re-use/re-mix) the resources of the others if they can get buy-in from their administrations, but this can quickly become a bureaucratic albatross around innovation and efficiency.

– – – – – – – – – –

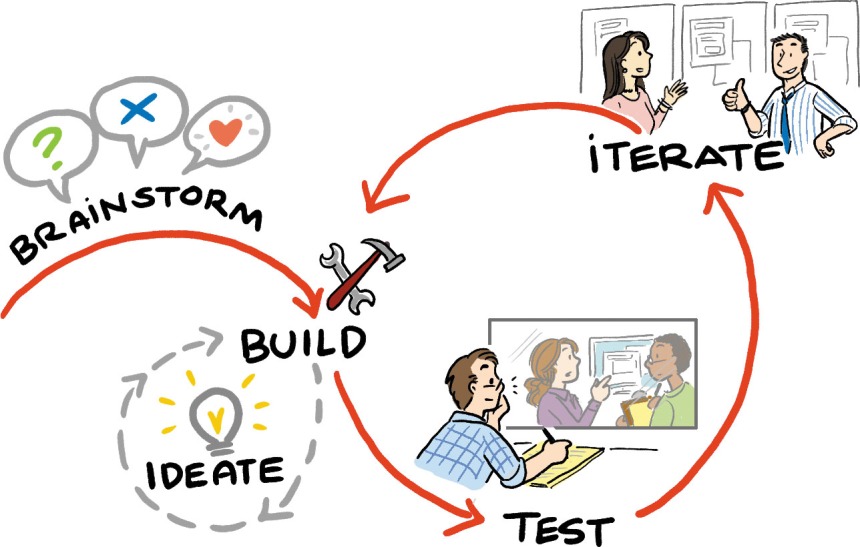

It’s time to try new things. We read about the harm that grading may do, then almost everyone still plans to provide traditional grades. We know that we can democratize the information in our classrooms, then we say it’s too hard to not go with the standard textbook. We are not wedded to anything beyond a semester, and maybe not even that long. Let’s try something closer to software design and engineering: design, test, iterate…

I would be ecstatic to build a course with a class. I vividly remember my freshman Biospyschology class, and that was many years ago. One of the most memorable features of the class was the unit on how illicit drug use affected the brain. The class voted on the drug we explored in the unit, and cocaine was selected. I still remember how cocaine affects the synapses. It was my first introduction to developing course content collaboratively, and it left an impression.

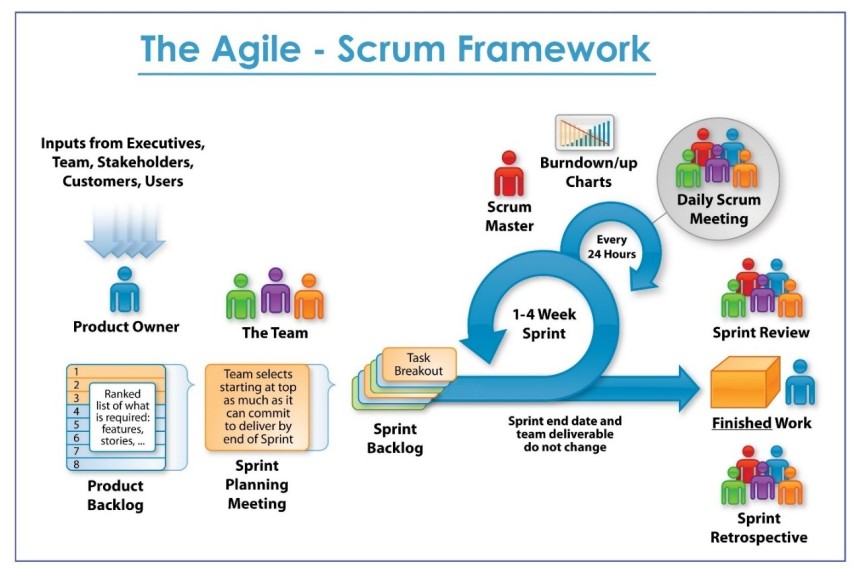

We have to start introducing a piece of collaborative design, a collaborator from another institution, a new piece of technology, a different form of assessment, and then keep building. Just as we design, test, and iterate in software we also have a backlog of ideas that we put out in two week sprints. We are not just iterating for weeks on end, but building on a foundation, which is continually being built onto.

– – – – – – – – – –

It was not raised during the Critical Open Pedagogy podcast, but institutions of higher learning have far reaching effects on the urban fabric of the communities where they exist and expand. They often bring jobs and stability, but can raise prices and wall off portions of communities. When we think about openness, the openness of facilities is also worth taking into account when many of our leading institutions receive local incentives and state and federal funding.

– – – – – – – – – –

While it represents a massive shift to address these factors, it could also provide institutions an opportunity to re-frame the value proposition of the university as a community anchor, a talent ignitor, a leveling force, and the type of dynamic place that tests and retests ideas.

Technology in our classroom: does it help or distract?

There are certainly different types of view on the usage of technology or the extent of allowable usage time of electronic devices (laptop or cellphones) in the classrooms. Although the use of technology is becoming more and more prevalent nowadays, there are instructors which make policies (like no mobile phone use) as they find it respectful to the instructor and other students.

As someone who is more on the side of advocating technology use in class, I must admit there are disadvantages associated with the technology use. Especially, in situations where we lose interest in following a lecture (or find it boring for whatever reason), then it becomes more and more tempting to check Facebook, Instagram, or do some online shopping. Given the appealing nature of these social media, we might get completely disconnected from the class and that’s where this could be a major challenge for the instructor to tackle. On the other hand, I believe there are many positive sides as well. There have been many situations for me when the instructor brings a new subject (or a terminology) which I was not aware of before and googling about them showed to a quick way for me to get the needed information.

In my opinion, as technology gets more and more advanced, its role in our classrooms would be more highlighted in the future and strict policies fro forbidding technology use might not be the best idea. Therefore, I believe establishing some rules for technology use would be a possible solution to avoid distraction. For example, using devices once in a while would be acceptable and helpful unless it becomes frequent.